Midi Canal map

About the Canal du Midi

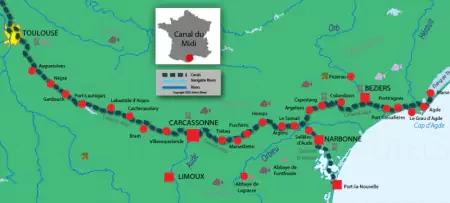

The Canal connects the le Canal latéral à la Garonne to the Mer Méditerranée.

Navigation on the Midi Canal starts at Marseillan and ends at Toulouse.

Construction began in 1667 and ended in 1681.

The Midi Canal is 241.00 kilometres long (149.75 miles) with a total of 241.00 kilometres of navigable waterway.

There is a total of 63 locks, with an average of 1 lock every 3.83 kilometres (2.38 miles).

The highest point on the Midi Canal is 189.00 metres (620′ 1″ ft) above sea level and the lowest point is at 0.00 metres (0′ 0″ ft) above sea level.

We've divided the Midi Canal into the following sections.

From Marseillan to Argens-Minervois

From lock 65 to lock 56

From kilometre point 240km to 152km

Geographical position ///subatomic.glided.nasally to ///hostilities.limiting.first

The water draft is 1.40 metres (4′ 7″ ft) and the air draft is 3.30 metres (10′ 10″ ft).

There is a total of 13 locks in this section.

General lock size

There are "Large" lock types.

Lock length 40.50 metres (132′ 10″ ft)

Lock width 6.00 metres (19′ 8″ ft)

From Argens-Minervois to Ayguesvives

From lock 55 to lock 9

From kilometre point 151km to 29km

Geographical position ///battles.banters.slurps to ///doucher.désireuse.duper

The water draft is 1.40 metres (4′ 7″ ft) and the air draft is 3.30 metres (10′ 10″ ft).

There is a total of 47 locks in this section.

General lock size

There are "Riquet-like" lock types.

Lock length 30.00 metres (98′ 5″ ft)

Lock width 5.45 metres (17′ 11″ ft)

From Ayguesvives to Toulouse

From lock 9 to lock 2

From kilometre point 28km to 1km

Geographical position ///cookies.bitumen.rafted to ///gasp.humans.milkman

The water draft is 1.40 metres (4′ 7″ ft) and the air draft is 3.50 metres (11′ 6″ ft).

There is a total of 3 locks in this section.

General lock size

There are "Large" lock types.

Lock length 40.50 metres (132′ 10″ ft)

Lock width 6.00 metres (19′ 8″ ft)

Features and structures to discover

Tunnel of Malpas

The 173 metre long tunnel was built between 1679 and 1680. This allowed the canal to pass under Enserune hill.

Geographical positions from ///amusante.dépoter.refaire to ///essence.grocery.bullseyeWe use links to what3words to help you discover the features. These links will open in a new page.

How old is the idea of linking the two seas? Old, very old, at least as old as the Romans. Many projects preceding the construction of the Midi Canal have existed over the centuries. The aim was almost always the same: a faster route between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic and avoiding navigation around Iberia and all its dangers. Most of these projects were not accepted as there was a fear that they would prove to be financial pits and were technically too difficult to make.

The main difficulty was the water supply needed for the canal's operation and the derivations needed to create this supply.

One man changed this: Pierre-Paul Riquet. Born in 1609, Riquet was a “general farmer”, charged to collect excise and indirect taxes. A shrewd man, his different offices in administration and tax collecting made him wealthy. He was also a skilled engineer, albeit amateurish regarding waterways, and he was able to get the attention of Louis XIV, the Sun King, with his plan for a canal in the Languedoc province. Riquet had help from several local figures, including the Archbishop of Toulouse, who was equally interested, notably in the potential profits to be made from linking the city of Toulouse to the Mediterranean. For the monarchy, the benefits of such a project were not solely financial. The King was seduced by the idea of being able to move safely and rapidly his fleets from one sea to another. A second important aspect was that by creating the canal, France could avoid the heavy toll imposed by Spain on merchant ships who wished to pass through Gibraltar. Finally, Jean Baptiste Colbert, the First Minister, who also had to be convinced, foresaw great commercial opportunities. Colbert oversaw the construction. Thus, the proposed canal project was an excellent opportunity to weaken France’s main enemy. A waterway canalization or the building of a canal was always a political and military enterprise as well as a financial one.

After several experiments and trials, Riquet was granted the King’s full authorization to begin the building. The lands on which the canal was to be built were turned into a fiefdom and given to Riquet, the newly made baron of Bonrepos. Despite the promising prospects of comfortable revenues, the construction of the canal proved to be a great challenge. The main difficulties were technical. Part of Riquet’s project was a clever and innovative system of water drainage to ensure the constant water supply of the canal, especially during the warm summer season. His idea was to use the waters of the Black Mountain range (south of the Massif Central) and channel them to the Seuil de Narouze (the watershed point) through an arrangement of lakes and rills. The most impressive feat of engineering was the lake of Saint-Ferréol and its dam fed by several rivers, completed in 1671 after four years of work. Riquet was a skilled engineer, but he also took inspiration from his predecessors, such as Hugues Cosnier who engineered the Briare Canal, or his associates like Pierre Campmas, who designed much of the water supply for the canal. However, he can be credited with engineering the first tunnel for a canal. One of the toughest difficulties was overcoming natural obstacles, among them crossing the Malpas mountain. Many eyes were set on Riquet, waiting for him to fail. The tunnel was completed in 1680 after a year of hard work. Mariners also had to be convinced to go underground with their barges, but they accepted after receiving a financial reward. Pierre-Paul Riquet died on 1 October 1680, financially ruined and with an unfinished canal. Several months later, in May 1681, the canal was completed and then inaugurated by high officials of the local government.

The Midi Canal, then known as the Languedoc Canal, was already transforming the land on which it was built. The King ordered the construction of a harbour in Sète. The city of Toulouse was probably one of the economic winners of this great enterprise. People were also attracted by working prospects and settled near the canal. There was an important urban development along the canal during the following two centuries. It remains a great example of how humans have shaped their natural environment for economic benefits. Yet, soon after its opening, it appeared that the canal was not the expected engineering masterpiece. It suffered from technical problems and was slow to navigate. Many transformations were made to overcome these shortages. It was the Marquis de Vauban who oversaw the first modifications of the canal. Vauban, mostly remembered for his important works in military fortifications, was also a keen observer and an advocate for improving the French waterway network. Vauban found that Saint-Ferréol Lake was not enough to supply the canal, so he improved it. To better the supply question, he also ordered the improvement of the smaller watercourses feeding the canal. By 1694, Vauban had added 49 aqueducts and several water bridges and strengthened most of the infrastructure.

The 18th century was a little financial golden age for the canal, although it still had many weaknesses. Riquet’s heirs were finally enjoying the benefits of Pierre-Paul’s work. The canal was an important feature of the region and was firmly grounded in the landscape and society. However, it was isolated from the rest of the waterway network and important cities, like Narbonne and Bordeaux, were not linked yet. In the 1770s, a junction with the Robine Canal and Narbonne was built. 40 years later, the canal was linked to the River Rhône and the city of Carcassonne. Remained the important question of joining the Ocean to finally construct the “canal of the Two Seas”. The opening of the lateral canal of the Garonne in 1856 was the conclusion point of this venture. The French Revolution marked a new era for the canal, then definitely christened the canal du Midi.

As a fief belonging to nobles who fled France, the State took over but did not manage it very well. In 1808, the ownership was given to the Midi Canal Company. Traffic had declined during these tormented years but a better Southern waterway network and technical advances gave a fresh impetus to the canal. In 1854, 67 million tonne-kilometres were recorded on the Midi Canal. Like many waterways, the arrival of train transportation brutally changed commercial navigation. The canal was to suffer greatly from this new concurrence. From 1850 to 1897, the canal was even bought by the Midi Railway Company. Even some modernizations to the Freycinet gauge could not prevent its decline.

The destinies of Southern waterways were not the same as those of the Northern parts of France as they are often smaller and shallower. Despite several encouraging boosts before and after the First World War, railways and then roads proved to be faster and more efficient. Commercial navigation was close to ceasing to exist and, with it, two centuries of traditions and a unique way of life for those whose livelihood was tied to the canal. Mail and passenger transportation, which have always coexisted with merchandise, were not sufficient to replace the loss of commercial freight. The canal’s only hope was leisure navigation and tourism. Several great travellers of past centuries, like Thomas Jefferson or Arthur Young, had been amazed by the canal. Its potential was great and, in 1996, when it was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, its future as a tourist jewel was assured.

From Toulouse in the West to the Mediterranean harbour of Sète in the East, shaded by plane trees lining its banks, the canal du Midi’s green waters wind through the beautiful countryside, past fields of sunflowers and the vineyards of Languedoc-Roussillon. Explore the busy port town of Béziers and enjoy the stunning views from the former cathedral of Saint-Nazaire, perched on a hilltop. To the west, at Fonseranes, you will find the marvellous flight of seven locks. See the world’s oldest canal tunnel at Malpas, and discover the exciting village of Capestang with its lovely, floodlit Saint Etienne Cathedral. Detour to Narbonne to see the impressive cathedral and Archbishop’s Palace. Famous for its medieval fortress set high on a hill with drawbridges, towers and cobbled streets, Carcassonne is unmissable. The medieval town of Castelnaudary is also worth exploring. It was built around a castle in the 12th century and was the birthplace of cassoulet, a meat and beans dish named after the earthenware pot in which it is cooked. Browse the traditional markets for local cheeses and enjoy tasting the region's wines.

The Canal du Midi passes through the wine-growing areas of the Languedoc, the Herault, the Aude, Minervois and Corbières. Basking in warm sunshine almost all year round, a cruise along the Canal du Midi is an ideal holiday for sun-seekers! Air-conditioned boats are advisable in July or August as temperatures can be high. A perfect boating holiday for experienced and first-time cruisers alike, this beautiful and tranquil waterway, with relaxed cruising through unique oval locks, stands testament to the technical mastery of its architects.

References

- Brunet, Roger (1959), « Le trafic des canaux du Midi » in Revue géographique des Pyrénées et du Sud-Ouest, n°30, pp. 179-188 [Online]

- Degos, Jean-Guy, Prat, Christian (2010), « Le Canal du Midi au 17e siècle » in Journées d’Histoire de la Comptabilité et du Mangement, France [Online]

- Marconis, Robert (1981), « Les canaux du Midi. Outil économique ou monument du patrimoine régional » in Revue géographique des Pyrénées et du Sud-Ouest, n°52, pp. 7-40.

- Sanchez, Jean-Christophe (2009), La vie sur le Canal du Midi, de Riquet à nos jours, Pau, Cairn, 158 p.

- « Canal du Midi » in UNESCO website [Online]

Barges cruising on the Midi Canal

| Name | Itinerary | Passengers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anjodi | Marseillan to Le Somail | 8 | View the itinerary |

| Athos | Argeliers to Marseillan | 10 | View the itinerary |

| Enchanté | Sallèles d'Aude to Trèbes | 8 | View the itinerary |

| Esperance | From Portiragnes to Carcassonne | 6 | View the itinerary |

| Esperance | From Portiragnes to Carcassonne | 6 | View the itinerary |

| Saraphina | Portiragnes to Homps | 4 | View the itinerary |

| Saraphina | Portiragnes to Homps | 4 | View the itinerary |

| Johanna | Carcassonne to Le Somail | 4 | View the itinerary |

Self-drive boats cruising on the Midi Canal

| Fleet | Cruise route | |

|---|---|---|

| Le Boat | Canal du Midi | View the Le Boat boats |

| Locaboat by Riverly | Midi Canal & Camargue | View the Locaboat by Riverly boats |

| Nicols by Riverly | Midi Canal | View the Nicols by Riverly boats |

| France Passion Plaisance | Camargue | View the France Passion Plaisance boats |

| France Passion Plaisance | Canal du Midi | View the France Passion Plaisance boats |

| Le Boat | Camargue | View the Le Boat boats |

More details about The Canal du Midi region